Ceylon’s 43 Group of Painters

SRI LANKA, known until 1972 as Ceylon, became an independent nation in 1948. Although in the preceding decades cataclysmic events had been occurring all over the world, in Ceylon to the intensity and ferment of the pre-war and war years were added the self-awareness and energetic hopefulness of an emerging new country. Ceylon was understandably keen to make its appearance as a modern nation with distinctive roots in the past yet an informed awareness of and sense of knowledgeable participation in the contemporary world.

The 43 Group of painters, who maintained a viable artistic brotherhood from 1943-1964, contributed to and were beneficiaries of this vitality and promise. One could say that their work represents the kind of fruitful amalgamation of foreign artistic influences that had not taken place in Ceylon since the Sigiriya frescoes of the fifth century and those at Polonnaruva seven hundred years later. Yet the 43 Group, unlike their predecessors, deliberately sought to integrate the foreign idiom with their own artistic tradition, thereby creating an art that would be both truly Ceylonese and truly modern. It was a bold endeavour and their movement deserves recognition as a significant attempt by artists of a colonial country to appropriate their own heritage and use it to make a relevant expression of individual and collective ideals in the larger world they now had no choice but to come to terms with.

With a few exceptions, their countrymen appreciated their overall aims as little as they appreciated their art. In essence, the battle for modern art was fought all over again forty years later on the other side of the globe, even with the same cries of outrage (review in the Ceylon Observor, 17.3.53: “… my son could draw better...”; editorial in the Ceylon Times, 28.10.56: “These artists are trying to fool the public...”). While the Group and its individual members had their champions from the beginning, it was really only after they had exhibited in London, Paris, and the Venice and São Paulo Biennales, receiving serious consideration and acclaim from international critics, that their country and even in some cases their own families began to acknowledge and respect their art. Even after their foreign triumphs there were derogatory newspaper accounts such as the one by the editor of the Ceylon Times that called them “The 43 Art Gropers” and said, with defensive pride: “I am one of those very inferior, lowbrow persons who are unable to appreciate, understand, or even put up with futuristic, surrealistic, impressionistic, abstract or 43 Group art” (“Janus”, Sunday Times, 28.10.56).

With a few exceptions, their countrymen appreciated their overall aims as little as they appreciated their art. In essence, the battle for modern art was fought all over again forty years later on the other side of the globe, even with the same cries of outrage (review in the Ceylon Observor, 17.3.53: “… my son could draw better...”; editorial in the Ceylon Times, 28.10.56: “These artists are trying to fool the public...”). While the Group and its individual members had their champions from the beginning, it was really only after they had exhibited in London, Paris, and the Venice and São Paulo Biennales, receiving serious consideration and acclaim from international critics, that their country and even in some cases their own families began to acknowledge and respect their art. Even after their foreign triumphs there were derogatory newspaper accounts such as the one by the editor of the Ceylon Times that called them “The 43 Art Gropers” and said, with defensive pride: “I am one of those very inferior, lowbrow persons who are unable to appreciate, understand, or even put up with futuristic, surrealistic, impressionistic, abstract or 43 Group art” (“Janus”, Sunday Times, 28.10.56).

As in all significant historical movements, one can credit the period in time for being propitious to change and one can name important persons whose personalities or dedication seem crucial to the movement’s success.

Certainly the 43 Group must acknowledge the catalysing influence of Lionel Wendt who, though not a painter himself, was what is of even more importance in circumstances where the new is struggling to emerge from the stranglehold of the old — a patron of the new in art. It was Wendt who gave the group its name (it was founded and presented its first exhibition in 1943), arranged for an exhibition hall (the rooms of the Photographic Society of Ceylon in a dilapidated warehouse in Union Place, no longer in existence), drew up the first catalogue and paid for it, and wrote to the papers defending the Group against a hostile reviewer.

Although he died suddenly in his sleep in 1944, at the age of forty-four, Wendt’s name lives on in present-day Sri Lanka in the Lionel Wendt Memorial Theatre and Art Gallery and in his superb book of photographs published by Lincolns Praeger in London, Lionel Wendt’s Ceylon, which is today a collector’s item.

As late as 1955, after the Ninth Exhibition of the 43 Group, a newspaper reviewer snidely invoked Wendt’s name: “Everywhere that Lionel Wendt the lambs were sure to go”, suggesting that it was Wendt’s influence and prestige that kept the Group together and in the limelight. At that time Wendt had been dead for eleven years. Yet in November 1952 the Group, invited by the Royal India, Pakistan and Ceylon Society, had exhibited in London at the Imperial Institute Gallery, South Kensington, and were invited on the strength of their London show to exhibit at the Petit Palais in Paris in 1953. It would seem that their power lay not only in Lionel Wendt’s promotional ability but in the art of the 43 Group itself.

Organisation of these important first European exhibitions (and later ones) was carried out by Ranjit Fernando, who became the Group’s representative abroad. Members of the 43 Group today stress that their successes in Europe were due in large measure to Fernando’s efforts, which were especially onerous because there was no official financial support to rely on. Funds had to be raised privately as neither the Ceylon Arts Council (the governmental body) nor the private Ceylon Society of Arts were willing to contribute to the expenses of either exhibition. Fortunately, the Asia Foundation and private donors made possible transport of the paintings from Ceylon to Europe.

In the February 1954 issue of the international art magazine based in London, The Studio, William Graham blamed the Ceylon Society of Arts for stifling all real talent, saying that even after eleven years the 43 Group was beset by ignorant opposition, insufficient patronage, and a complete lack of official recognition at home.

Certainly the 43 Group must acknowledge the catalysing influence of Lionel Wendt who, though not a painter himself, was what is of even more importance in circumstances where the new is struggling to emerge from the stranglehold of the old — a patron of the new in art. It was Wendt who gave the group its name (it was founded and presented its first exhibition in 1943), arranged for an exhibition hall (the rooms of the Photographic Society of Ceylon in a dilapidated warehouse in Union Place, no longer in existence), drew up the first catalogue and paid for it, and wrote to the papers defending the Group against a hostile reviewer.

Although he died suddenly in his sleep in 1944, at the age of forty-four, Wendt’s name lives on in present-day Sri Lanka in the Lionel Wendt Memorial Theatre and Art Gallery and in his superb book of photographs published by Lincolns Praeger in London, Lionel Wendt’s Ceylon, which is today a collector’s item.

As late as 1955, after the Ninth Exhibition of the 43 Group, a newspaper reviewer snidely invoked Wendt’s name: “Everywhere that Lionel Wendt the lambs were sure to go”, suggesting that it was Wendt’s influence and prestige that kept the Group together and in the limelight. At that time Wendt had been dead for eleven years. Yet in November 1952 the Group, invited by the Royal India, Pakistan and Ceylon Society, had exhibited in London at the Imperial Institute Gallery, South Kensington, and were invited on the strength of their London show to exhibit at the Petit Palais in Paris in 1953. It would seem that their power lay not only in Lionel Wendt’s promotional ability but in the art of the 43 Group itself.

Organisation of these important first European exhibitions (and later ones) was carried out by Ranjit Fernando, who became the Group’s representative abroad. Members of the 43 Group today stress that their successes in Europe were due in large measure to Fernando’s efforts, which were especially onerous because there was no official financial support to rely on. Funds had to be raised privately as neither the Ceylon Arts Council (the governmental body) nor the private Ceylon Society of Arts were willing to contribute to the expenses of either exhibition. Fortunately, the Asia Foundation and private donors made possible transport of the paintings from Ceylon to Europe.

In the February 1954 issue of the international art magazine based in London, The Studio, William Graham blamed the Ceylon Society of Arts for stifling all real talent, saying that even after eleven years the 43 Group was beset by ignorant opposition, insufficient patronage, and a complete lack of official recognition at home.

British exhibitions in 1954 included individual shows by George Keyt at the Institute of Contemporary Arts (arranged by an Englishman, Martin Russell, who had become acquainted with Keyt and his art while serving in Ceylon during the war) and Justin Daraniyagala at the Beaux Arts Gallery, with a group show running concurrently at the Artists International Association Gallery. The Heffer Gallery in Cambridge held an exhibition of one hundred 43 Group paintings which was opened by E.M. Forster. Like the first European exhibitions Ranjit Fernando was solely responsible for organising these smaller shows.

Critics who reviewed the exhibitions included John Berger, Maurice Collis and Myfanwy Piper in major papers and journals such as the Manchester Guardian, Art News, Time and Tide, Spectator, New Statesman and Nation, and The Times. Yet requests for exhibitions from galleries in Amsterdam, Mexico, Dublin, Rio de Janeiro and Israel had to be declined because sufficient funds could not be found.

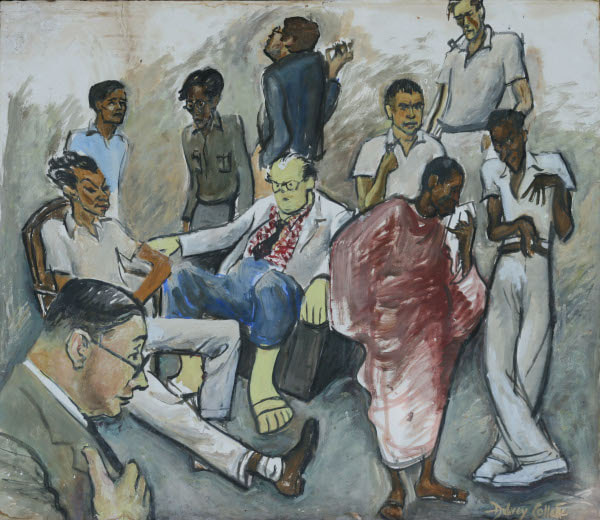

Of the seven painters who exhibited in all or most of the Group’s fifteen home exhibitions over twenty-one years, that is, George Keyt, Justin Pieris Daraniyagala, Harry Pieris, George Claessen, Aubrey Collette, Ivan Peries and Richard Gabriel, three (Keyt, Harry Pieris and Gabriel) are still at work and living in Sri Lanka. Collette is a newspaper cartoonist in Melbourne; Ivan Peries a painter who lives at Southend in England; George Claessen, retired as a draughtsman, still paints and resides in London. Daraniyagala died in 1967, three years after the Group held its last group exhibition.

Harry Pieris, who deserves to be named along with Lionel Wendt as prime mover and sustainer of the 43 Group, has preserved an invaluable collection of newspaper cuttings, catalogues, and other information pertaining to twentieth century art in Sri Lanka. He is only too happy to share his archives and personal reminiscences with interested people, and has described to me how the idea of the 43 Group first arose. To appreciate their aims and hopes, one should have some acquaintance with art in Ceylon during the half- century or so preceding 1943.

Critics who reviewed the exhibitions included John Berger, Maurice Collis and Myfanwy Piper in major papers and journals such as the Manchester Guardian, Art News, Time and Tide, Spectator, New Statesman and Nation, and The Times. Yet requests for exhibitions from galleries in Amsterdam, Mexico, Dublin, Rio de Janeiro and Israel had to be declined because sufficient funds could not be found.

Of the seven painters who exhibited in all or most of the Group’s fifteen home exhibitions over twenty-one years, that is, George Keyt, Justin Pieris Daraniyagala, Harry Pieris, George Claessen, Aubrey Collette, Ivan Peries and Richard Gabriel, three (Keyt, Harry Pieris and Gabriel) are still at work and living in Sri Lanka. Collette is a newspaper cartoonist in Melbourne; Ivan Peries a painter who lives at Southend in England; George Claessen, retired as a draughtsman, still paints and resides in London. Daraniyagala died in 1967, three years after the Group held its last group exhibition.

Harry Pieris, who deserves to be named along with Lionel Wendt as prime mover and sustainer of the 43 Group, has preserved an invaluable collection of newspaper cuttings, catalogues, and other information pertaining to twentieth century art in Sri Lanka. He is only too happy to share his archives and personal reminiscences with interested people, and has described to me how the idea of the 43 Group first arose. To appreciate their aims and hopes, one should have some acquaintance with art in Ceylon during the half- century or so preceding 1943.

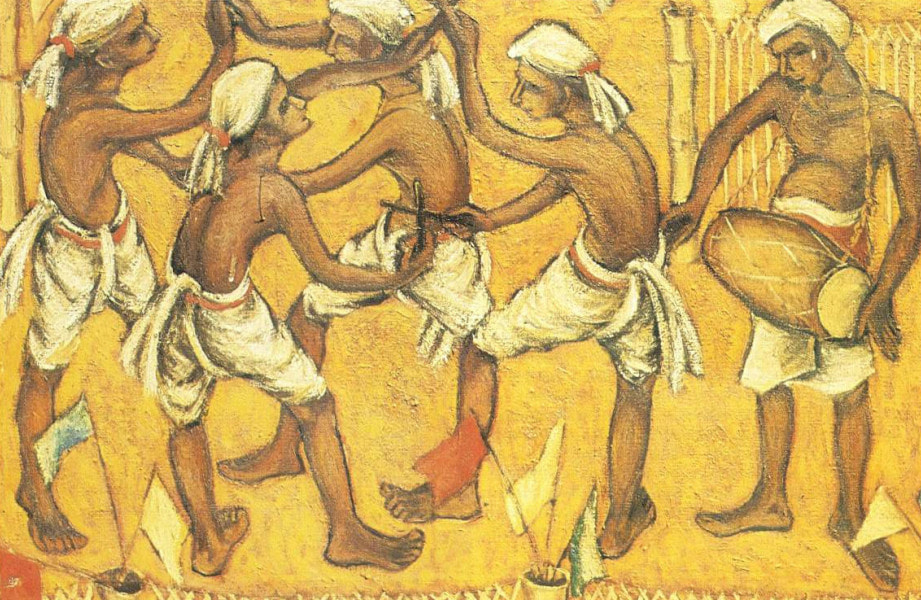

While the peasants and villagers, as was the case from time immemorial, were acquainted with art only as it depicted sacred stories in Buddhist temples and shrines or informed the rituals of daily life, the educated, moneyed classes in Colombo had gradually acquired European attitudes towards art as towards everything else. In the 1880s there was a group composed of Ceylonese and Europeans called the Colombo Drawing Club or Portfolio Sketch Club, whose members circulated their own sketches and once a month met to select the “Painting of the Month”. They held their first public exhibition in August 1887 at the Coffee Tavern on Prince Street. This group seems to have metamorphosed a few years later into the Ceylon Society of Arts, with the objective of “encouraging pictorial art in Ceylon”. Given the times, it turned out that they were promoting specifically Victorian studio painting. Only the subject matter — elephants, costumed drummers, tropical vegetation — distinguished it from British academic painting of the same time. A published description of the Society, written in 1907 in Twentieth Century Impressions of Ceylon, stated:

... with proper encouragement and the cooperation of the Government in establishing a picture gallery in the island, where aspirants might study works of art by leading masters and derive practical help in the pursuit of their ideals, the artistic instinct in the Ceylonese, so long dormant and neglected, is susceptible of cultivation. What has hitherto been wanting is the incentive to high aspiration that can only arise from knowledge of what is really good and sound art … a number of prominent European and Ceylonese ladies and gentlemen have volunteered to offer prizes for the best work; and this has persuaded many amateur artists to take to their studies with greater zest and keenness.

The names of the earliest individual Ceylonese artists are associated with the Ceylon Society of Arts: Mudaliyar A.C.G.S. Amarasekara (Harry Pieris’s first teacher), J.D.A. Perera, Gate Mudaliyar Tudor Rajapakse and David Paynter. Harry Pieris as a young man was a member of the C.S.A. He exhibited with them, collected money for them, and was on their selection committee.

A lone anti-establishment voice in Ceylon of the 1920s was that of an Englishman, C.F. Winzer, the Ceylon Government Inspector of Art in the Education Department. Winzer believed that the eternal qualities of Ceylonese art, as found at Anuradhapura, Sigiriya and Polonnaruva, should be studied by contemporary artists and adapted to modern life and art, thus achieving a continuity between the past and present. The revolutionary idea Winzer espoused was that such continuity was closer to the decorative conceptions of modern Western art than to the realistic, true to life prettiness and cheap harmonies of academic achievement.

Whether or not this idea was consciously in the minds of the 43 Group artists, it was supported by their accomplishments, vindicating what must have sounded heretical in 1931 when Winzer stated it at his farewell speech to the Ceylon Art Club, which he had founded in 1929. After Winzer’s departure in 1932, the Club folded.

A lone anti-establishment voice in Ceylon of the 1920s was that of an Englishman, C.F. Winzer, the Ceylon Government Inspector of Art in the Education Department. Winzer believed that the eternal qualities of Ceylonese art, as found at Anuradhapura, Sigiriya and Polonnaruva, should be studied by contemporary artists and adapted to modern life and art, thus achieving a continuity between the past and present. The revolutionary idea Winzer espoused was that such continuity was closer to the decorative conceptions of modern Western art than to the realistic, true to life prettiness and cheap harmonies of academic achievement.

Whether or not this idea was consciously in the minds of the 43 Group artists, it was supported by their accomplishments, vindicating what must have sounded heretical in 1931 when Winzer stated it at his farewell speech to the Ceylon Art Club, which he had founded in 1929. After Winzer’s departure in 1932, the Club folded.

In the late 1920s and 1930s Lionel Wendt, whose pen and tongue were equally sharp, engaged in newspaper controversies with A.C.G.S. Amarasekera about modern art. Wendt collected Hanfstaengel prints of recent European paintings — Impressionists, Post-Impressionists, Fauves, Cubists, and Orphists — and showed them to those who cared to see. George Keyt’s cousin, Dr Hugh Modder who was a surgeon in England, sent him prints of early twentieth century painters, including issues of the Cahiers d’Art of 1932 and 1933. When Harry Pieris returned to Ceylon in 1938 after a number of years studying art abroad, he agreed with other young painters that everything was still discouragingly the same at home, and eventually they decided to form their own little group. In 1943, then, the inaugural meeting was held at Lionel Wendt’s home.

It was decided to keep organisation to a minimum: no President, only a twelve-member Committee including an Honorary Secretary and Honorary Treasurer. These were W.J.G. Beling, A.C. Collette, Ralph Claessen, J.E.P. Daraniyagala, R.D. Gabriel, S.R. Kanakasabai, George Keyt, Manjusri Thero, Ivan Peries and Lionel Wendt. Harry Pieris was Honorary Secretary and George Claessen Honorary Treasurer. Beling, who had succeeded Winzer as Inspector of Art in the Education Department, stopped painting in 1945. Manjusri, who was at the time a Buddhist priest, exhibited in the first two exhibitions before resigning from the Group in 1944. Ralph Claessen and S.R. Kanakasabai also stopped exhibiting with the Group after the first few shows.

Members would be proposed and elected, with one blackball keeping a person out. Subscriptions would be five rupees per year. Meetings were monthly, first at Wendt’s, then at the home of Harry Pieris. Wendt, not being a painter, was the final arbiter in choosing paintings for exhibition and otherwise resolving any disagreements that arose among the artists.

The minutes of the first meeting stated that “the Group exists for the furtherance in every way of art in all its branches”. The unstated aim was to break away from the academism of nineteenth century European studio painting and to create a synthesis of twentieth century Western European art with Ceylon’s ancient heritage of Hindu and Buddhist culture. Additionally, by mounting interesting exhibitions for the public, both by member artists and by other artists, it was hoped that the Group could help develop taste and knowledge of art in the public and encourage new talent.

It was decided to keep organisation to a minimum: no President, only a twelve-member Committee including an Honorary Secretary and Honorary Treasurer. These were W.J.G. Beling, A.C. Collette, Ralph Claessen, J.E.P. Daraniyagala, R.D. Gabriel, S.R. Kanakasabai, George Keyt, Manjusri Thero, Ivan Peries and Lionel Wendt. Harry Pieris was Honorary Secretary and George Claessen Honorary Treasurer. Beling, who had succeeded Winzer as Inspector of Art in the Education Department, stopped painting in 1945. Manjusri, who was at the time a Buddhist priest, exhibited in the first two exhibitions before resigning from the Group in 1944. Ralph Claessen and S.R. Kanakasabai also stopped exhibiting with the Group after the first few shows.

Members would be proposed and elected, with one blackball keeping a person out. Subscriptions would be five rupees per year. Meetings were monthly, first at Wendt’s, then at the home of Harry Pieris. Wendt, not being a painter, was the final arbiter in choosing paintings for exhibition and otherwise resolving any disagreements that arose among the artists.

The minutes of the first meeting stated that “the Group exists for the furtherance in every way of art in all its branches”. The unstated aim was to break away from the academism of nineteenth century European studio painting and to create a synthesis of twentieth century Western European art with Ceylon’s ancient heritage of Hindu and Buddhist culture. Additionally, by mounting interesting exhibitions for the public, both by member artists and by other artists, it was hoped that the Group could help develop taste and knowledge of art in the public and encourage new talent.

Between November 1943 and September 1950 the 43 Group had annual exhibitions of their own work; additionally they sponsored exhibitions of Kandyan dancing, reproductions of Ajanta frescoes, French Impressionist prints, and photographs of Khmer sculpture. In the early fifties, as described above, they exhibited in London and Cambridge, Paris, Venice, and São Paulo; then from 1955-1959 there were five more Group exhibitions in Colombo. In 1964 the last two exhibitions of the 43 Group were held, number 14 in January, and the 21st Anniversary Exhibition in November.

Over the years more than forty artists had shown their works, primarily paintings and drawings, but also sculpture, ceramics and tapestry. Justin Daraniyagala had brought international acclaim to his country when he won one of two UNESCO awards among 4728 works exhibited at the 28th Venice Biennale in 1956, and one of his paintings was reproduced by UNESCO as a colour print. George Keyt gained renown in India and England where his works were placed in important collections. Richard Gabriel was made an Honorary Member of the Accademia delle Arti del Disegno of Florence, as a result of his contributions to the Venice Biennale in 1956. The City of Paris bought canvases by Ivan Peries and Gabriel, which were placed in the Petit Palais.

What members of the 43 Group held in common was not a style but a conviction that Ceylonese art could be modern without sacrificing specifically Ceylonese values and traditions. Many of today’s younger Ceylonese artists exhibited in 43 Group shows of the fifties and sixties (for example, Sushila Fernando, Swanee Jayawardena, Neville Weeraratne, Stanley Kirinde and Tissa Ranasinghe) and thus had their first public exposure under 43 Group auspices. These and other younger artists formed a Young Artists’ Group which held other exhibitions in the 1950s and 1960s.

The 43 Group’s influence was less in the form of a specific style than as an example. They showed that Ceylonese life, and values, with roots in ancient tradition, could be portrayed in a twentieth century manner. This created an atmosphere both of confidence that there was such a thing as modern Ceylonese art, and the permission to create it. Those with interest and talent in the arts tried new and unprecedented things and had remarkable, far-reaching success in such areas as handloom weaving (Edith Ludowyk and Barbara Sansoni); film making (Lester James Peries); batik design (Ena de Silva, Laki Senanayake, Anil Jayasuriya, Jean and I. Arasanayagam); theatre (E.F.C. Ludowyk and Ediriweera Sarachchandra), and architecture (Geoffrey Bawa and Minnette de Silva). Many of these names are internationally known as innovators, as respected artists, and as Ceylonese. They all came to maturity in the 1950s and 1960s when 43 Group influence was at its strongest.

The controversy surrounding the 43 Group exhibitions served to spawn an interest in contemporary art among a small segment of the public who began for the first time to collect art objects for their homes. Although enthusiasm for art is still much smaller in modern-day Sri Lanka than in the West, it has become de rigeur in certain circles to own original works of art, if possible by 43 Group artists. More importantly, there is a continuing achievement by dedicated practitioners of the arts, and their work is definitely not in the tradition of the nineteenth century academic studio.

Harry Pieris, whose charming Colombo home serves as an informal gallery and exhibition hall of 43 Group art, is still as keen as ever to encourage the appreciation and advancement of art in Sri Lanka. To this end he has established a non-profit foundation, called Sapumal, in the hope of being able permanently to preserve his priceless collection and archives in one place and to continue to foster the study and development of the arts.

Forty-three years after 1943 few Sri Lankans are aware of the progressive and vital force that inhered in the efforts and convictions of the 43 Group and its supporters. What was once ridiculed and dismissed can today be acknowledged as one of the most fecund contributions to national self-awareness and achievement in post-war, post-independence Ceylon.

Over the years more than forty artists had shown their works, primarily paintings and drawings, but also sculpture, ceramics and tapestry. Justin Daraniyagala had brought international acclaim to his country when he won one of two UNESCO awards among 4728 works exhibited at the 28th Venice Biennale in 1956, and one of his paintings was reproduced by UNESCO as a colour print. George Keyt gained renown in India and England where his works were placed in important collections. Richard Gabriel was made an Honorary Member of the Accademia delle Arti del Disegno of Florence, as a result of his contributions to the Venice Biennale in 1956. The City of Paris bought canvases by Ivan Peries and Gabriel, which were placed in the Petit Palais.

What members of the 43 Group held in common was not a style but a conviction that Ceylonese art could be modern without sacrificing specifically Ceylonese values and traditions. Many of today’s younger Ceylonese artists exhibited in 43 Group shows of the fifties and sixties (for example, Sushila Fernando, Swanee Jayawardena, Neville Weeraratne, Stanley Kirinde and Tissa Ranasinghe) and thus had their first public exposure under 43 Group auspices. These and other younger artists formed a Young Artists’ Group which held other exhibitions in the 1950s and 1960s.

The 43 Group’s influence was less in the form of a specific style than as an example. They showed that Ceylonese life, and values, with roots in ancient tradition, could be portrayed in a twentieth century manner. This created an atmosphere both of confidence that there was such a thing as modern Ceylonese art, and the permission to create it. Those with interest and talent in the arts tried new and unprecedented things and had remarkable, far-reaching success in such areas as handloom weaving (Edith Ludowyk and Barbara Sansoni); film making (Lester James Peries); batik design (Ena de Silva, Laki Senanayake, Anil Jayasuriya, Jean and I. Arasanayagam); theatre (E.F.C. Ludowyk and Ediriweera Sarachchandra), and architecture (Geoffrey Bawa and Minnette de Silva). Many of these names are internationally known as innovators, as respected artists, and as Ceylonese. They all came to maturity in the 1950s and 1960s when 43 Group influence was at its strongest.

The controversy surrounding the 43 Group exhibitions served to spawn an interest in contemporary art among a small segment of the public who began for the first time to collect art objects for their homes. Although enthusiasm for art is still much smaller in modern-day Sri Lanka than in the West, it has become de rigeur in certain circles to own original works of art, if possible by 43 Group artists. More importantly, there is a continuing achievement by dedicated practitioners of the arts, and their work is definitely not in the tradition of the nineteenth century academic studio.

Harry Pieris, whose charming Colombo home serves as an informal gallery and exhibition hall of 43 Group art, is still as keen as ever to encourage the appreciation and advancement of art in Sri Lanka. To this end he has established a non-profit foundation, called Sapumal, in the hope of being able permanently to preserve his priceless collection and archives in one place and to continue to foster the study and development of the arts.

Forty-three years after 1943 few Sri Lankans are aware of the progressive and vital force that inhered in the efforts and convictions of the 43 Group and its supporters. What was once ridiculed and dismissed can today be acknowledged as one of the most fecund contributions to national self-awareness and achievement in post-war, post-independence Ceylon.