Minnette De Silva

Pioneer of Modern Architecture in Sri Lanka

Orientations, August 1982

One of the earliest lone voices in the now clamorous cry for the preservation of traditional crafts and artistic values in South Asian countries was that of Ananda K. Coomaraswamy. In 1905, in his Open Letter to the Kandyan Chiefs, he appealed to the Ceylonese to preserve old buildings such as temples, shrines, private houses and pilgrims' shelters with their traditional architecture, which, as he noted, made use of the handiwork of all the arts and crafts — that of

|

the stone mason and carpenter, the blacksmith and silversmith, the painter and potter, even the weaver who contributed to produce buildings of a lovely and harmonious character, part as it were of the very soil it grew from and perfectly harmonious in style from the finials on the roof to the inlaid key plates on the doors and from the carved moonstones at the entrances to the woven chatty covers used for the procession starting out to fetch in new rice from the temple lands.

|

Needless to say, Coomaraswamy's plea has not been often heeded, and, as elsewhere in the world, many of the country's finest old buildings have been replaced or carelessly ‘restored'.

New domestic dwellings have all too often been inspired by imperfectly understood and unsuitable Western prototypes — a practice which, though deplorable, can be easily understood. Sri Lanka, like other tropical countries where until recently the majority of people lived in simple wattle-and-daub cottages in villages, lacks a tradition of domestic architecture that could be handed over ready-made to meet the needs of middle-class town and city dwellers. In developing an appropriate modern architecture it has been necessary to amalgamate the peculiar requirements of a tropical and Asian way of life with the needs of families and individuals in a modernising Asian society.

It is not surprising that one of the very first Ceylonese architects to address herself to such a task was a person whose background fostered a recognition of the validity and special claims of both the traditional and modern points of view. Minnette De Silva, who has practiced architecture in Sri Lanka from shortly after its independence in 1948, is notable — as an individual and as an architect — on a number of accounts.

She is one of two exceptional daughters of the influential political leader, George E. De Silva, who represented Kandy in the legislature for nearly thirty years and also served as Minister of Health. Both sisters chose careers that were unusual and unorthodox for Asians, particularly Asian women, of their generation: one in art history, the other in architecture. The De Silva family itself was unconventional by Ceylonese standards, for the parents were from different communities and indeed remain well known even today for their pioneering of social and political rights for all persons, regardless of their birth and background. Mrs. De Silva, niece of the early scholar of Ceylonese history, Andreas Nell, was one of the leaders in the movement which succeeded in 1928 in granting the franchise to Ceylonese women as well as to men.

Minnette De Silva studied architecture first in Bombay and then at the London Architectural Association School. She was the first Asian woman to be elected an Associate of the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA). Additionally, she has lived and worked for extended periods in India, lived in Greece, and travelled widely in Western and Eastern Europe, in Iran, Afghanistan and Pakistan. During her recent tenure as a lecturer in the history of Asian architecture at the University of Hong Kong, she visited the People's Republic of China.

A biography of Minnette De Silva would include accounts of her acquaintance with many of the century's well-known figures — statesmen and poets, scholars and artists from Asia and the West. A close friend of Le Corbusier, one of the most influential figures in twentieth-century architecture, she was his guest at Chandigarh and owns some of his letters and memorabilia.

With her varied background and the example in her family of unusual and socially relevant accomplishment, Minnette De Silva has been well placed to make an original and valuable contribution to the architecture of present-day Sri Lanka. This she did, but not without a struggle.

After Minnette De Silva received her diploma and her membership of RIBA in the late 1940s her father insisted that she return to her country to make her contribution to newly independent Ceylon. During the 1950s she developed her personal architectural style which heralded many of the most successful and appealing features of the best Sri Lankan architecture of today. Others were quick to follow with their own adaptations and designs and original contributions, but just as Minnette De Silva was the first Ceylonese woman architect so she was the first Ceylonese architect to endorse what Coomaraswamy had urgently and unavailingly stressed fifty years before — the importance of preserving traditional crafts by using traditional materials and local craftsmen for contemporary buildings. She was among the first to amalgamate knowledge acquired from the West with the building traditions of Ceylon and India.

It may seem too obvious even to mention, but one of the first considerations of a tropical architecture must be the climate: sun and glare, heal, heavy rain and the direction of the strong monsoonal winds. Although for the most part colonial architects understood this, post-independence architects too often have not, in their wish to copy clichés of Western houses — meaningless in the Ceylonese context — the conventional small family home with small separate rooms, full of furniture and draperies, the house surrounded by a lawn and fence and approached by a space-consuming driveway. Such a concept suits the casual, informal communal nature of the Asian family's way of life as little as it does the climate. A Ceylonese house should be able to ‘expand' to cope with crowds of relatives on special occasions (as for an almsgiving when a kitchen may be required to produce rice for forty people).

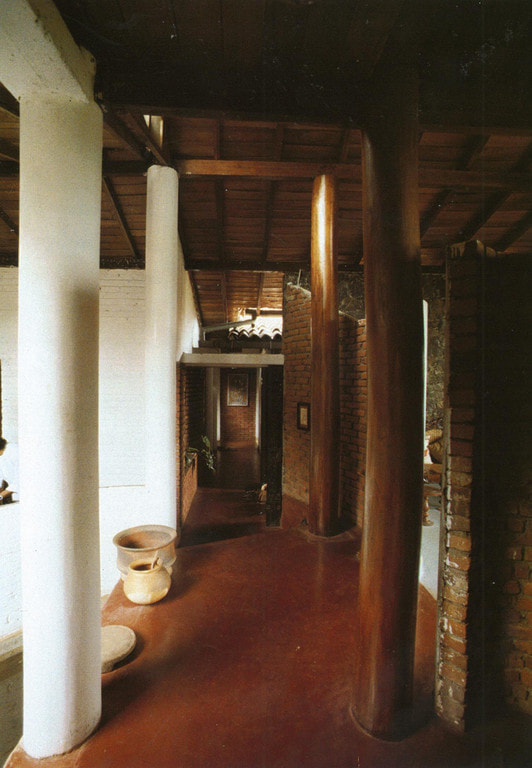

Many of Minnette De Silva's houses reflect this appreciation of the ‘open' house where columnar supports, open or with movable panels, allow outdoor and indoor activities to be extensions of each other, and where the refreshing bounty of nature is an integral part of everyday life. In a De Silva house living space is flexible. She encourages the custom of uncluttered rooms where cane and open-weave divans and lounging chairs, stools, mats, cushions and small carpets for reclining are used sparingly. These are all easily moved about, suiting today's small family which does not have the numerous domestic helpers of colonial times, yet which must adapt frequently to the more gregarious requirements of social religious occasions that include the larger family.

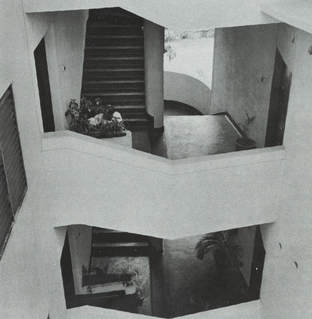

In Minnette De Silva's houses one finds pierced walls of concrete, brick, wood or wrought iron. She first used single brick openwork outside walls in a low-cost housing scheme in the 1950s, thus allowing ventilation and light without the need for expensive windows and grilles. In many of her homes shutters provide privacy for verandas which are often the most used living space. She has frequently adapted to modern buildings the old Kandyan mada midula or central courtyard open to the sky, and private open-air areas for bathing.

One of the most characteristic features of a De Silva house is the use of decorative motifs from local and traditional arts and crafts. Locally-woven hemp Dumbara mats become attractive floor and chair coverings, or panels for walls, doors and ceilings. Traditional lacquer work poles in red, gold and black have been used as simple tapering stair balusters. Ornamental motifs from other contexts have been put to decorative uses in her building: terracotta or wrought-iron details in a bo-leaf shape, ornamental tiles cast from ancient woodcarvings, and rows of small triangular niches derived from those originally meant to hold oil lamps. Acting upon her conviction that not only the architect and craftsman but the artist be brought together in building, she has commissioned for her houses murals from painters such as George Keyt and Stanley Kirinde.

Minnette Do Silva's work is notable as well for the juxtaposition of different materials — large and small stones, or rough, natural rock and smooth plaster; timber that is painted or lacquered or used for its own natural colour and grain set off against a contrasting wall or a background of leafy vegetation. Also, as in old buildings, one does not have an impression of neat geometrical progression and orderly rectangles, but of contour, irregularity, surprise — a flow and scale adapted to human spontaneity and flexibility. Under a steeply pitched tiled roof, which is an attractive adaptation to domestic use of Kandyan palace and temple architecture, she has incorporated the charming Western and ancient Eastern feature of the attic flat or open attic study which utilises the space above the living area.

Minnette De Silva's current consuming professional challenge is to design a new Kandyan Art Association complex on its existing premises. This is a centenary project for the Association, which was founded in 1882 with the aim of giving employment to the best craftsmen working in the traditional Kandyan style. The choice of Minnette De Silva for this important and influential project is not only a recognition of her special contributions and abilities but also a reflection of the Association's commitment (in the spirit of Coomaraswamy's plea) to foster the Kandyan artistic heritage. The new complex, which will incorporate existing structures, will include a theatre, a restaurant and a craftsmen's display area as well as the sales establishment.

In addition to the Kandyan Art Association complex, Minnette De Silva has recently finished designing an unusual tourist resort, Forest Park, in the forest near the ancient sacred city of Anuradhapura, mainly for the Buddhist pilgrims of the Hokke Club of Japan, and for others who appreciate peace and quiet. She envisages low-scale buildings, roofed with local red tiles, to be almost hidden amidst the vegetation. Local people and their traditional skills are to be used extensively in the construction, maintenance and daily life of the project so that the often disruptive effect of a tourist hotel on the physical and social life of a natural area will be mitigated as far as possible. Her earlier ‘caravanserai' or jungle village camping site near the ancient rock fortress of Sigiriya is significant for its use of wattle-and-daub and thatch.

Throughout her busy professional career as a practising architect, Minnette De Silva has kept extensive files on the indigenous architecture of Asia, photographing peasant houses, shrines, grain storage structures and brick kilns in India, Bangladesh, Thailand and Sri Lanka. Thus she is in the process of compiling a valuable ‘directory' of vernacular architectural solutions by traditional peoples to universal problems of daily living, as well as finding inspiration for her own building.

Additionally, as a founder of the Bombay-based magazine Marg, and a contributing editor to the Eastern section of the eighteenth edition of Sir Banister Fletcher's monumental History of Architecture, Minnette De Silva has also maintained a continuing interest in the history and current state of Asian architecture and arts. She has collected quantities of pictorial and documentary material, and is at present writing a reference book on Asian architecture, along the lines of Banister Fletcher's history, which is to be published by the Athlone Press. Friends urge her to write down as well the details of her interesting life, and a special memoir of her association with Le Corbusier.

The guiding architectural philosophy that has emerged from Minnette De Silva's wide-ranging experience is a respect for the simple and natural. Like the dwellings of traditional peoples, and even those of birds and animals, a De Silva building looks as if it was made to the scale of those who use it, with natural materials and by natural means. The complicated tools and heavy machinery required to assemble the rigid and heavy concrete-festooned structures that dominate South Asian cities today have no place in the construction of a De Silva building.

The result is a successful amalgamation of art and nature, an architecture that is always conscious of its natural raw materials and setting, as well as of the human beings who built it and whose lives are affected daily by it. ※